Former

entrances on

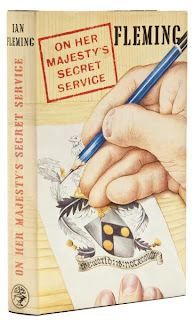

The

Strand and Surrey Street

London

“When

the lift goes up and the train leaves,

Aldwych station is as deserted as an ancient mine. You can hear the drip

of water and the beat of your heart.”

Rogue Male, Geoffrey Household

(Chatto & Windus, 1939)

Upon

returning to England the anonymous protagonist of Geoffrey Household’s classic

thriller pays a visit to his solicitor Saul in Lincoln’s Inn Fields in the

Holborn area of London. However, the building is being watched by agents of the

unspecified European power (which we assume from its description to be Nazi

Germany) from whose clutches he has just escaped.

Upon

entering the underground station at Holborn, he discovers he is being followed

by his chief pursuer Major Quive-Smith as well as another agent who had

previously been spotted feeding the birds outside Saul’s offices. The dramatic plot

sequence that follows uses the layout of the tube network as its basis.

At

the time Household wrote Rogue Male,

a short branch of the Piccadilly line ran from Holborn to its terminus at

Aldwych. After attempting to throw off his pursuers inside Holborn station,

Household’s hero boards the Aldwych train only to discover that a third agent

wearing a black hat and blue flannel suit is waiting for him. Whilst the train

is still in the station he then lures “Black Hat” into the tunnel where the

agent is electrocuted by the live rail. Now wanted for murder, he is propelled

to put the next part of his escape plan into operation and go to ground in

rural Dorset.

|

| Entrance to the former Aldwych Station on Surrey Street |

Aldwych

station was opened as Strand in 1907 and, as Household describes, was served by

a train that shuttled back and forth from Holborn. The year after Rogue Male was published the station was

temporarily closed and served as an air raid shelter during the war, with its

tunnels providing safe storage for items from the British Museum including the

Elgin marbles. Although the branch line was the subject of several extension

plans, none of these came to fruition and the station was permanently shut in

1994 due to low passenger numbers. The former entrances, which are Grade II

listed, are still visible on The Strand and Surrey Street, with the Strand

entrance still bearing the station’s original name.

Rating (out of 10): 4